The 71st Carnival of Ancient & Medieval History Blogging.

As a full-blooded member of the vinous Wein-garten family, I am kicking off this Carnival with two grape stories. The first may be more archaeology than history -- but who can doubt that turning grapes into wine changed the history of humankind forever?

The first tipple knocked back 6,100 years ago

Wine-making started 1,000 years earlier than we thought: Anthropology.net ('When & Where Grapes Domesticated') reports on a 6,000 year old uncorked 'wine barrel' discovered at the Areni-1 cave near the Iranian border in Armenia (the same place where the 5,500 year-old leather moccasin was found last year). It forms part of the oldest complete wine production facility ever found, including grape seeds, withered grape vines, remains of pressed grapes, a rudimentary wine press, a clay vat apparently used for fermentation, wine-soaked potsherds, and even a cup and drinking bowl.

The precise identity of the wine-swilling shoe-wearing people remains a mystery but the archaeologists have some interesting ideas on how wine was first used. More on that, and details of radiocarbon dating, paleobotanical, and chemical residue analysis at the UCLA.edu portal.

After examining the grape seeds, the species turned out to be Vitis vinifera vinifera, the domesticated variety of grape still used to make wine today. And therein lies a grave problem....

Lack of Sex Among Grapes Tangles a Family Vine

The New York Times (25 January) set the tone,

For the last 8,000 years, the wine grape has had very little sex. This unnatural abstinence threatens to sap the grape’s genetic health and the future pleasure of millions of oenophiles.

After testing genetic variation in over 1,000 samples of the domesticated grape, Vitis vinifera vinifera, and its wild relative, V. vinifera sylvestris, Sean Myles of Cornell University, discovered that 75% of the 583 varieties of cultivated grapes were as closely related as parent and child or brother and sister. "Previously people thought there were several different families of grape," Dr Myles said. "Now we’ve found that all those families are interconnected and in essence there’s just one large family."

This web of interrelatedness indicates that the grape has undergone very little breeding since it was first domesticated. Albeit one big happy family, this makes the grape especially vulnerable to pests and diseases (think of the French phylloxera epidemic of the 19th century). It's an oenophilic disaster waiting to happen. The whole story is at 'Genetic Study of the Grape Reveals Weakness in Our Wine Supply' on JetLib News, and the publication on the PNAS website.

OK, the pub is now closed, the Armenians having pipped the Egyptians at the post: wine remains from the tomb of King Scorpion I (ca. 3150 BCE) appeared long after Opening Time.

That news was the beginning of a bad month for the pharaohs.

Is Pharaoh DNA For Real?

The results of the first DNA analysis of ancient Egyptian royalty - a huge study of 11 royal mummies dating from around 1300 BC - were published with great fanfare in February 2010. The findings were dramatic. As well as detecting DNA from the malaria parasite in four of the mummies, the researchers produced a family tree. They identified Tutankhamun's father as the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten, concluded that Tut's parents were brother and sister, and determined that two mummified foetuses found in his tomb were probably his stillborn children.

It seemed that we were finally getting definitive answers to questions relating to health, family relationships, and causes of death.

Or were we?

Jo Marchant (Decoding the Heavens) explains why this study has triggered not so much excitement as scepticism and frustration for many in the ancient-DNA community. Is it the dawn of 'molecular Egyptology' and our first insight into the genetic origins of the pharaohs -- or of researchers under huge pressure for results seeing what they want to see? Is Pharaoh DNA for real? is the best analysis I've read of why -- so far -- things only seem to get murkier.

'Egypt without Secrets is like a day without sunshine', as an ancient proverb might have it.

Unknown Secret Chambers in the Great Pyramid?

Where else?

The known chambers and passages inside the Great Pyramid are shown, left -- but French architect and pyramid expert Jean-Pierre Houdin argues that these are merely related to the pyramid's construction and were not those used for the funeral procession. His claim that the Great Pyramid is hiding secret rooms and passages could be settled by scanning the walls with ground-penetrating radar. Jo Marchant investigates, in the Great Pyramid's Secret Chambers.

And yet another Mystery from Ancient Egypt:

Did the Ancient Egyptians Know of Pygmy Mammoths?

Among the exotic gifts presented to pharaoh, as shown on the painted walls of Rekhmire's tomb (mid-late 15th C BCE) in the Valley of the Nobles, is a unique depiction of a small, tusked, hairy elephant (left). The beast is pictured waist-high to the Syrian traders marching beside him in the procession.

The African elephants Loxodonta and the now extinct Middle Eastern population of the Asian elephant Elephas maximus were both known to the ancient Egyptians, but Rekhmire's elephant doesn't seem to be either. Its apparent hairiness, convex back and domed head makes it look like a juvenile Asian elephant -- but it is also shown with huge tusks. Darren Naish at Tetrapod Zoology (via Andie at Egyptology News) explores the possibility that it was a late-surviving pygmy Mediterranean island-dwelling species. Chronology just about makes the link feasible. Art historians will look askance but it's fun to think of the last dwarf elephant on earth ending up being presented to pharaoh -- and recorded in his vizier's tomb at Thebes.

Shiver My Timbers

In the ancient Mediterranean parrots were an exotic bird. They were rare, multicoloured and could even repeat human words or swear like sailors. Ctesias of Cnidus (late 5th C BCE) was the first to describe the human-tongued bird in a work, now lost, which comes down to us somewhat garbled:

The parrot is about as large as a hawk, which has a human tongue and voice, a dark red beak, a black beard, and blue feathers up to the neck, which is red like cinnabar. It speaks Indian like a native, and if taught Greek, speaks Greek.

Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog ('First Greek Encounter with a Parrot') helps to ungarble Ctesias' colour code and nail down the species of bird (I'll take it on trust, too, Beachcomber). Beachcomber also supplies a cackle of parrot references -- from poetry (e.g., the glory and the pride of the fowls of the air, the radiant Ruler of the East, is dead is dead) to the bizarre feast with parrot meat mentioned in Eubulus -- but, surely, Beachbomber, the comic poet was 'only kidding'.

Bad Omens! Bad Omens!

No, not from parrots, no matter how foul-mouthed.

But from dead birds falling from the sky.

... like the thousands of blackbirds, starlings, grackles, and cowbirds hitting the ground in Arkansas on New Year's Eve. Surely, a sign!

What, wonders Vicky Alvear Shecter of History With A Twist, if it had happened in Rome?

If thousands of birds had fallen from the sky in ancient Rome, everybody—from emperors, to warriors, to peasants and slaves — would have been in a state of complete and total panic.

Streets would have run with blood as priests slaughtered animal victims to appease the gods. And yes, they'd certainly have asked -- as did Arkansans, too -- why did it happen on New Year's Eve? What can it mean? "God is angry," say some. "We must change our behaviour to appease him," say others. How can anyone deny that it's the first sign of the Apocalypse and end of the world?

In short, some people seem to have learnt nothing in the intervening millennia.

Speaking of bad-omened Romans, I made the sign against the evil-eye when I saw this headline in the Guardian newspaper:

Caligula's tomb found after police arrest statue-smuggler.

But, sadly, this was not Caligula's tomb. This was media hype.

The police arrested a man near Lake Nemi, south of Rome, as he loaded part of a 2.5 metre [8.2'] statue into a lorry [truck]. True, the emperor had a villa in the area, as well as a floating temple and a floating palace, but the only evidence for a tomb seems to be a misunderstanding of the Italian word, tombarolo -- 'tomb robber' (more generally, illegal digger). And why did the police finger Caligula? Because the statue was shod with a pair of the caligae, the military boots worn by the emperor when, as a boy, he accompanied his father on campaigns in Germany: the soldiers were amused and gave him his nickname Caligula, or "little boot".

Putting the (big) boot in.

Big Boot 1: 'RogueClassicism' (Caligula Tomb Silliness) advised the Guardian not take the word of the police when it comes to historical/archaeological matters. He pointed out that Romans generally didn’t entomb folk on country estates. And, anyway, Suetonius told us what happened to Caligula’s perforated corpse (stabbed at least 30 times):

His body was conveyed secretly to the gardens of the Lamian family, where it was partly consumed on a hastily erected pyre and buried beneath a light covering of turf; later his sisters on their return from exile dug it up, cremated it, and consigned it to the tomb. [thus, in or near the gardens]

Big Boot 2: Mary Beard, in 'A Don's Life' (This Isn't Caligula's Tomb) adds that you can't tell a headless statue by its boots: loads of Roman statues wear such boots. And, for good measure, as a commenter on her post added, Caligula wore them as a boy, not as a man.

Big Boot 3: 'New at LacusCurtius and Livius' (Oh, please...) notes that the last line of the media report is, “The tomb raider led them [the police] to the site, where excavations will start today.” In other words, research still has to start.

So, this was about as accurate a report as you'd expect from Caligula's horse.

I have more bones to pick

Bone Girl (An African in Avon?) writes about the discovery of the skeleton of an African man who died in ca. 300 CE in what is now Stratford-on-Avon. Naturally, the public wants to know who he is -- and the archaeologists oblige: "He could have been a merchant, although, based on the evidence of the skeletal pathology it is probably more likely that he was a slave or an army veteran who retired to Stratford."

Wow(-ish)!

Bone Girl wonders, first of all, how they determined that this skeleton is that of an African man: isotopes, DNA, morphology? We don't know. All we have are osteological results, which "revealed the man was heavily built and used to carrying heavy loads." And between 40-50 years old when he died. From these meagre pickings, our African(?) has become a probable slave or old soldier.

Granted, slave, soldier, and merchant were the main classifications of men who moved around the Roman Empire. But there were certainly free civilians, students, and others (like women and children) who circulated in this large geographic space. Additionally, slaves could (and were often) freed, so the ideas of social class and free/slave are quite mutable in the Roman Empire.

Quite so. Read the whole story at Bone Girl.

But, before we leave Stratford, we have to ask, "Is the man even African, and, if he is, what does that mean? According to Rosemary Joyce (British, Roman, or African?), people in the past were not as homogeneous as we imagine them:

The Roman empire extended across northern Africa; Roman legions recruited from across the empire; and trade throughout the empire surely was accompanied by movement of people from place to place.

In Roman Britain, the interesting question about this man's status would have been: was he a citizen or a slave – a civil status, not racialized as it became as a consequence of the Atlantic slave trade. The interfering screen here is our modern use of race as the determinative classification of identity. Lots more spot-on analysis at British, Roman, or African?.

And lots more bones

Tenthmedieval (More skeletons and this time Vikings) reports on the 54 bodies found in a burial pit along the Ridgeway in Dorset, England: all of them were men, nearly all in their teens or twenties, all executed, and their severed heads were stacked separately (in the photo, upper left).

Isotope analysis showed they were non-local guys, most likely from much further north so it's hard to doubt that these were some Vikings "who’d lost the big game quite badly". Radiocarbon dates cluster around the year 1000 CE, when Dorset was ravaged by Vikings (998), and by Cnut's invading army (1015). Tenthmedieval tells us how the victims died (a grisly tale). Still, we can only speculate if they were raiders, or a mercenary group or even a garrison, perhaps connected with the infamous events of 1002.

But as to the fable that there are Antipodes, that is to say, men on the opposite side of the earth, where the sun rises when it sets to us, men who walk with their feet opposite ours, that is on no ground credible.

Just so. But more to the point, when you consider Columbus' voyage, is his view of the size of the earth, which was still based on Ptolemy's Geography:

"Ptolemy calculated that a degree was 50 miles (not 70 as we know today), which gave him an earth with a circumference of only 18,000 miles. Ptolemy also stretched Asia eastward for 180 degrees (not 130 degrees as we know today). Therefore, Columbus thought India was far closer than it really was."

So Columbus sailed with a map probably quite like the one made -- in 1492, no less -- by Martin Behaim (above, left) a German geographer in the service of the King of Portugal; and note the legendary 'St Brendan's Island' smack-dab in the middle of the Atlantic. After reading Babinski's post, it's perfectly clear why Columbus thought he had reached the islands off the coast of India. And logical too.

Vasco da Gama, however, did get to India not many years later, arriving in Calicut (Kerala) in 1498. His ship's Journal preserved the story of his meeting with the king, the Zamorin, of the land. A wonderfully detailed account of their meeting is given, with running commentary by Maddy, in 'The Many Faces of the Zamorin' on the Historic Alleys blog.

Curious crowds had gathered around the palace:

When we reached the palace we passed through a gate into a courtyard of great size, and before we arrived at where the king was, we passed four doors, through which we had to force our way, giving many blows to the people. When, at last, we reached the door where the king was, there came forth from it a little old man, who holds a position resembling that of a bishop [i.e. a Brahmin], and whose advice the king acts upon in all affairs of the church. This man embraced the captain when he entered the door. Several men were wounded at this door, and we got in only by the use of much force.

Maddy reproduces western paintings and tapestries purporting to illustrate the historic encounter. The closest in date to the event is a commemorative medal minted in Portugal ca. 1510 (above, left). The female musicians seem more than a bit fanciful, though, perhaps inserted from temple sculptures.

Vivisection isn't so bad when you consider the alternative

For example, hanging.

In January, 1474, an archer of Meudon (southwest of Paris) was condemned for many robberies, and especially for robbing the church at Meudon, and sentenced to be hanged.

But he wasn't hanged.

Instead, he was vivisected alive for the good of better men ... and survived -- not to tell the tale, but to collect a pension from the king. Even better.

Executed Today tells this amazing story. The anonymous villain himself, bowels back in and all sewn up, vanishes from history. His story, however, morphed into a myth of French medicine: the unspecified ailment became identified with kidney stones; a heroic and brilliant French physician was fabricated as the genius behind the procedure; even Louis XI turns up personally to observe (above, left). Read about what happened, why it became myth, and, just as strange, why it disappeared from medical history.

Thus ends the 71st History Carnivalesque.

But wait! I can't end on that macabre note. How about this for a happy ending?

This comfy sofa based on the Roman Colosseum is Italian furniture maker Tappezzeria Rocchetti's new zenith in tatty representations of glorious antiquities.

Absolutely perfect for flopping down in front of the television and watching someone being disembowelled. Alive.

My thanks to all who nominated great candidates for Carnivalesque.

Illustrations

All illustrations are from the blog posts mentioned, except for the reproduction of the globe of Martin Behaim, for which credit goes to Wikipedia.

.

.

.

Blogging Ancient/Medieval History

The next ancient/medieval edition of Carnivalesque -- the monthly showcase for top history blogging -- will appear right here at Zenobia: Empress of the East on Sunday, 20th February.

So please get cracking and send me notices of the best early-history blogging you've read so far in 2011 -- all of the fine, insightful, or just plain provoking posts as they struck you in the new year.

Feel free to nominate even [and especially!] your own writings as well.

You can email me directly at judith@judithweingarten.com or use the ancient/medieval nomination form.

If you're not familiar with history carnivals, hop over to the History Carnivals Aggregator where you'll find up-to-the-minute news on history-related carnivals. Did you know, for example, that the early modern Carnivalesque now up at Airs, Waters, Places has everything from Irish birds falling from the sky to the poisoned jellies and tarts cooked up by 'a sexually promiscuous, murderous, syphilitic sorceress'?

Undoubtedly we, too, shall cover the gamut of groovy activities -- plus whatever else takes Zenobia's fancy -- for the ancient and medieval worlds on 20 February.

Hold this date!

Photo: Encontro estadual de maracatus, Carnaval do Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Credit: Antônio Cruz/Agência Brasil via Wikipedia.

.

.

.

Where in the world will you find texts written in Greek, Latin, Palmyrene and Syrian Aramaic, Middle Persian, Parthian, Hebrew, and Safaitic -- all inscribed at much the same time? And where do you think you will come across dozens of temples dedicated to Greek and Roman gods, a bevy of Mesopotamian deities (some of dazzling obscurity), Palmyran gods and gads*, a Mithraeum, a frescoed synagogue and the earliest Christian house-church anywhere in the world?

Perhaps in Rome, you would guess.

But no, not Rome.

Rather, at a distant outpost on the Euphrates frontier, in the ruined city of Dura Europos:

The town (today in Syria) is perched on a hill high above the river. Its name, Dura Europos, is an artificial twin, joined by archaeologists to describe the city known to Parthians and Romans as Dura (meaning 'fortress') and to Greeks as Europos -- in honour of the Macedonian birthplace of Seleucus Nicator, a general under Alexander the Great, who is reputed to have founded the city.

At the Crossroads of East and West

Seleucus Nicator (358-281 BCE), the first king of the Seleucid dynasty, filled the town with Macedonian veterans in order to control the strategic river crossing and to connect the equally brand-new cities of Antioch near the Mediterranean coast with Seleucia on the faraway Tigris (near modern Baghdad)

The Parthians conquered Dura in 141 BCE and it remained in their hands -- except for a brief grab by Trajan ca. 115 CE -- until captured by the Romans in 165 CE, after which it was garrisoned by Roman and Palmyran troops (the latter, a cohort of horse-mounted archers, the XXth Palmyrorum). Dura met its end after a sustained siege by the Sasanian Persians in 256/57 -- after which it was abandoned, covered by sand and mud, and disappeared from sight.

Treasures on Display

Between 1928 and 1937, archaeologists from Yale University and the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres excavated Dura, bringing to light not just the temples, houses, fortifications, and military quarters of this cosmopolitan city, but an extraordinary collection of frescoes, mosaics, and carved reliefs, as well as inscriptions in a babble of languages and astonishingly well-preserved objects of war and peace, all mingled together in the daily life of a bustling town.

Now, an exhibition at the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College is showcasing some of the most significant treasures excavated in the 1920s and 1930s from the ancient city: Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity displays 75 artefacts from the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery. Together, they tell the story of this vibrant multicultural city inhabiting a crossroad between major eastern and western civilizations.

Crosscurrents in a microcosm

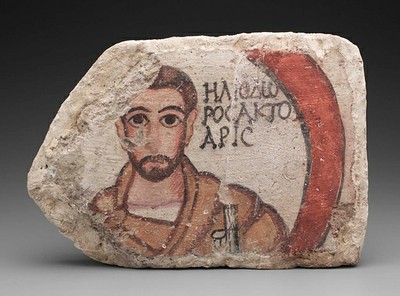

I'd like to showcase just one piece that caught my eye (below). Of course, there's a good Palmyran story behind it, too.

The foundation of the city was still being celebrated in 159 CE (that is, still in the Parthian period) -- not just by descendants of those first Macedonians, but by Palmyrans living at Dura. Expatriate Palmyrans dedicated this handsome stone relief at the Temple of the Gads* (Tyche in Greek; the 'Good Fortune' of the city), which they had built at Dura -- more than 200 km as the crow flies from Palmyra. Inscriptions, primarily in Aramaic, identify the figures and date the dedication.

The relief depicts the Gad* of Dura as a bearded Zeus Olympios dressed in semi-Greek costume. The god/gad is seated on a throne flanked by two eagles; a throne flanked by duplicated birds or animals is not at all a Greek idea but rather reflects a very ancient Near Eastern divine custom.** The reputed founder of the city, Seleucus Nicator, in military outfit, is seen crowning the god. Zeus was that king's divine patron and the relationship between the king and his favourite deity remained intimate long after his reign, even extending to a royal cult of Seleucus Zeus Nicator. A Palmyran priest, named Hairan, burns incense on an altar to the left of the scene(besides his Semitic name, Hairan wears a tall cylindrical cap, the sign of a Palmyran priest).

Outsider Offerings

So, the first thing to note is that we have a group of outsiders (= Palmyrans; probably merchants, for their temple is quite near the main marketplace) who are showing respect to the major god/gad of their place of residence. And, while the relief honours the Greek god/gad as Dura's highest deity and equally relates to the cult of the Seleucid dynasty, the offering is made by a Palmyran priest. And, of course, the relief will hang in the main Palmyran temple at Dura.

That's not all we can read on this relief.

The second thing to note is that it was made of Palmyran limestone so it had been ordered and (from the look of it) carved in Palmyra and transported to Dura. It was probably made to mark an event that took place before the end of the Parthian period -- and that must have been connected with the rebuilding of the Temple of the Gads ca. 150 CE. The new, expanded temple was double the size of the original, modest religious structure established a century earlier. Most, if not all, of the construction work was financed by one important Palmyran family: that of Hairan, the son of Maliku, son of Nasor. That's the same Hairan who offers incense to the Gad of Dura on the relief above. This rich aristocrat, by the way, is almost certainly the great-grandfather of Zenobia's husband, the heroic warrior prince, Odenathus.

Sex Change at Dura

A male 'Fortune' of a city is incompatible with the Greek notion of Tyche but fits the Semitic tendency to view the most important deity of a locality as its gad. Despite Dura-Europos being ruled by the Parthians for almost 300 years, the iconography of the gad and the figure of Seleucus Nicator suggest that the Palmyran residents of Dura considered the main god of the city to be the Greek god, Zeus Olympios; evidently, they still thought of Dura as a Greek city. This surely was not a Palmyran invention but must have been the common idea elsewhere current in the city. In short, the indigenous inhabitants of Dura continued to cherish their Macedonian/Greek heritage and identity right through the Parthian period.

Semitic Gads were inextricably connected with a particular place or people ... but, apparently, at Dura, not necessarily with a particular sex.

Because of their origin in the Greek goddess Tyche, Syrian Tychai, too, are always represented as female -- whereas the Semitic gads, being manifestations of locally venerated gods and goddesses, can be either male or female. Yet, by the Roman period at the latest, Dura's Fortune of the City is being venerated as Tyche (Greek), gd (Palmyrene), or genius (Latin); and all three 'names' can appear together even on a single altar, which shows that they have become indistinguishable. This may well be due to the popularity of Tyche in other Greek cities, not least at Antioch, the greatest city of Syria.

So, the gad of Dura undergoes a sex change

This famous fresco [also from the Palmyran Temple (ca. 239 CE)], shows Julius Terentius, the tribune of the Palmyran cohort, offering incense to three Palmyran gods (upper left) and to the gads of Palmyra and Dura (lower left). Both gads are represented as goddesses. This change of the sex of the Gad of Dura may reflect a shift from the old Semitic idea that the most prominent local deity is automatically the local gad to the Greek convention of identifying the Fortune of a city as female. And so, like any good Greek city goddess, the two gads are depicted wearing mural (city) crowns.

New York University

15 East 84th Street

New York, NY 10028

Hours: 11am-6pm

Friday: 11am-8pm

Closed Monday

Free Admission

The ISAW presentation has been made possible through the support of the Leon Levy Foundation.

* Gad is an Aramaic word meaning 'luck' or 'good fortune' and can refer to a divine being, most commonly the tutelary god or goddess of the city. The temple is now usually called the 'temple of Bel'.

** While the eagle is a typical attribute of Zeus, the Greek god has one eagle, not two, which either sits on his hand or beside his throne. The duplication and placement of the eagles flanking the throne is oriental in origin.

*** If you can't make the show, the exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue of the same title, which includes 18 scholarly essays by an international group of participants and a colour plate of each object on display. With a range of specialists—from Yale, Boston College, Harvard and Brandeis universities, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and universities in Great Britain and the Netherlands, the catalogue — like the exhibition — seeks to reintegrate thinking about the city of Dura-Europos.

I am grateful to Margaret Neeley, Publications & Exhibitions Administrator,McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College for sending me the excellent press kit and photographs. Co-curators of Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity are Yale University Art Gallery Associate Curator of Ancient Art Lisa R. Brody and Boston College Assistant Professor of Classical Studies Gail L. Hoffman.

I have made much use of Lucinda Dirven's discussion of the 'Hairan relief' in her book, The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: a Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria (Brill, 1999), Ch. 4. For more information on Dura Europos, see Simon James' pages at the University of Leicester website.

Illustrations

The photo of the citadel at Dura Europos is from University of Leicester. Other photo's are courtesy of the McMullen Museum of Art.

.

.

.

Part I click here.

The Sculptured Cliff

A snapshot of the cliff face at Naqsh-e Rostam.*

And I quote:

This was the ritual and symbolic heart of the Achaemenid Empire with a wealth of sculptural, architectural, and inscriptions unparalleled elsewhere in the empire.

And I quote:

This was the ritual and symbolic heart of the Sasanian Empire with a wealth of sculptural, architectural, and inscriptions unparalleled elsewhere in the empire.

No, do not adjust your computer. Both statements are correct.

ACHAEMENIDS FIRST.

Located ca. 8 km [5 miles] from the palaces of Persepolis, four royal Achaemenid tombs are cut into the rock face just where the flat-topped mountains begin their slide down into the plains. It may be that the Achaemenids were inspired to convert these precipitous cliffs into their royal necropolis and cult centre after hearing the beautiful natural echo in the surrounded valley.**

Four tombs belonging to Achaemenid kings are cut into the cliff walls, all at least 15 metres (50') above the ground. The tomb on the right (above) belongs to Darius the Great (ruled 522-486 BCE), who was the first to order a monumental tomb to be carved on the site.

The tombs are known locally as the 'Persian crosses', named after the shape of the façades of the tombs. The entrance to each tomb is at the centre of the cross, which opens onto a small chamber where the king lay in a sarcophagus (long empty, the tombs were smashed open and looted when Alexander the Great conquered Persia). The horizontal arm of each cross is believed to show the image of the entrance to the main palace at Persepolis.

On the façade of the tomb, in the upper register, Darius sacrifices on a blazing fire altar to his Zoroastrian god,

A great god is Ahuramazda, who created this earth, who created yonder sky, who created man, who created happiness for man, who made Darius king, one king of many, one lord of many.

King of kings and lord of many, this was truly a world empire. We see Darius on his throne, carried on a platform by the 30 nations who were his subject peoples -- each dressed in their distinctive costumes and headgears. Cuneiform inscriptions identify the nations: Persia, Media, Parthia, Bactria, and so on for the central realms, then to the east all the way to the Indian states of Sind and Gandara, westwards to Syria, Arabia, and Egypt, and in the north the Armenians, Cappadocians, Lydians, and Ionians. The cruciform design of his tomb was copied on the cliff wall by his successors: Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE), Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BCE; above left), and Darius II (r. 423-404 BCE) -- although the exact attributions are not certain since these tombs lack inscriptions.

In addition to the royal tombs, there is one mysterious tower of stone masonry known as 'the Ka'ba of Zoroaster' (Ka'ba = 'cube', 'sanctuary') which stands opposite the sculptured cliff. Instead of the dusty scrub land you see between them today, there were perhaps once trees and the green of an artificial garden (paradeisos). This massive square tower (12.5 high x 7.3 wide [41'x 24']) gives the impression of three stories, but the lower half is solid while the upper half houses just a single square room with no provision for lighting: the windows are false windows. An exterior staircase of 30 steps (now partly destroyed) led up to a doorway opening into the one square room. The lack of any ventilation excludes the tower's use as a fire temple. The best explanation, I think, is that the Ka'ba was a kind of 'coronation tower' -- with the new king ascending the staircase to be crowned -- with the royal paraphernalia stored in the square room. If true, the tower, like the tombs, would have served a dynastic rather than purely religious function.

Gap Years

After the Achaemenids, no king of either the Seleucid (330-139 BCE) or Parthian (ca. 238 BCE-224 CE) dynasty left any monument in or on the hillsides of Naqsh-e Rostam. Thus, when Ardashir I overthrew the last Parthian king, Ardawan IV, in 224 CE, more than 550 years had passed since Naqsh-e Rustam had been touched by royalty.

SASANIANS SECOND

Although so far away in time, the Sasanian capital of Istakhr was still only a hop, skip, and a jump (2 km) from the site, so its funerary reliefs and strange tower could never really have been forgotten. It is impossible to believe that the pre-imperial Sasanians had not felt the impact of the monumental rock reliefs. And so it proved: once in power, the Achaemenid reliefs offered the new dynasty visually stunning -- and ideologically useful -- prototypes:

What is remarkable about the Sasanian dynasty's additions to the site is not their monumentality but the extent to which they sensitively, seamlessly, and unrelentingly incorporated the Achaemenid material into their larger vision.

Sasanian King # 1

Soon after the Sassanians came to power, Ardashir I began the permanent visual fusion of the two dynasties by carving the first rock relief on the western end of Naqsh-e Rostam. It pictures both his investiture as king and his triumph over his enemies. Ardashir is the horseman on the left, shown receiving the royal diadem, the xvarnah -- the visual symbol of the king's divine election -- from the god Hormuzd (the Middle Persian name for Ahuramazda). The god hands the divine glory to the new king, who takes the diadem with his right hand, while saluting Hormuzd with his left fist and pointed index finger in the sign of respect. Both king and god are calmly crushing their defeated enemies under their horse's hooves. This is a fresh interpretation of the millennia-old act of trampling a defeated enemy: Ardashir finishes off Ardawan IV in an exact mirror image of Hormuzd trampling the Zoroastrian evil demon, Ahriman.

It seems certain that the site and this triumphant image were chosen by Ardashir to unite the divine beneficial radiance, the xvarnah of the Achaemenids, with his own person and with his family. Quite appropriately, then, Ardashir adopted the Achaemenid concept of the 'kingdom of Iran' (Ērānšāhr) and took on their ancient title of the 'king of kings of Ērānšāhr', as if this were the birthright of the new Sasanian dynasty.

Sasanian King # 2

His son and successor, Shapur I, inherited the concept of Ērānšāhr from his father but, inspired by his military successes and ambitions, expanded his father's claim to one of dominion over Ērān ud Anēran ('Iran and non-Iran'), which is to say that he claimed a kind of universal sovereignty. Non-Iran literally referred to Shapur's new conquests in Central and South Asia and the eastern Roman Empire. But it also contained the latent claim of his rightful dominion outside the Iranian sphere -- which included, most notably, the Emperor of Rome whom he regarded as his tributary.

Near the beginning of Shapur's reign, a Roman army led by the Emperor Gordian III invaded Persia (243/244 CE). Despite initial successes, the Romans were defeated and their army all but obliterated. According to Shapur, Gordian died in battle. Whether true or not, Shapur forced his successor (and possible assassin) Philip the Arab to pay a huge ransom in order to withdraw alive along with his remaining forces. Shapur boasted of this victory in a trilingual inscription (Middle Persian/Parthian/Greek) inscribed on the walls of the Ka'ba of Zoroaster -- thereby simultaneously laying claim to this Achaemenid structure and further implying a link between the two dynasties. This text makes clear that he believed that he reduced the Roman Empire and its Emperor to tributary status.

One might say that he confirmed this claim (at least in his own mind) when, in 258/259 CE, he destroyed another mighty Roman army, led this time by the Emperor Valerian, capturing the emperor and his court, and deporting them along with the remnants of their army deep into Persia. Valerian died in ignominious captivity. Victorious Shapur made two great rock reliefs to mark his victories. One (at Bishapur) shows him on horseback trampling the body of the hapless Gordian III. It is otherwise identical with the scene of triumph carved at Naqsh-e Rustan (above left) and boldly placed right in the centre of the site: it stands below and between the tombs of Darius I and the tomb attributed to Artaxerxes I (as seen at the top of this post), and right across from the Ka'ba. This relief shows Shapur on horseback grasping the wrist of Valerian -- which indicates he has been taken prisoner -- while Philip the Arab is kneeling in submission before the King.

His son and successor, Shapur I, inherited the concept of Ērānšāhr from his father but, inspired by his military successes and ambitions, expanded his father's claim to one of dominion over Ērān ud Anēran ('Iran and non-Iran'), which is to say that he claimed a kind of universal sovereignty. Non-Iran literally referred to Shapur's new conquests in Central and South Asia and the eastern Roman Empire. But it also contained the latent claim of his rightful dominion outside the Iranian sphere -- which included, most notably, the Emperor of Rome whom he regarded as his tributary.

Near the beginning of Shapur's reign, a Roman army led by the Emperor Gordian III invaded Persia (243/244 CE). Despite initial successes, the Romans were defeated and their army all but obliterated. According to Shapur, Gordian died in battle. Whether true or not, Shapur forced his successor (and possible assassin) Philip the Arab to pay a huge ransom in order to withdraw alive along with his remaining forces. Shapur boasted of this victory in a trilingual inscription (Middle Persian/Parthian/Greek) inscribed on the walls of the Ka'ba of Zoroaster -- thereby simultaneously laying claim to this Achaemenid structure and further implying a link between the two dynasties. This text makes clear that he believed that he reduced the Roman Empire and its Emperor to tributary status.

One might say that he confirmed this claim (at least in his own mind) when, in 258/259 CE, he destroyed another mighty Roman army, led this time by the Emperor Valerian, capturing the emperor and his court, and deporting them along with the remnants of their army deep into Persia. Valerian died in ignominious captivity. Victorious Shapur made two great rock reliefs to mark his victories. One (at Bishapur) shows him on horseback trampling the body of the hapless Gordian III. It is otherwise identical with the scene of triumph carved at Naqsh-e Rustan (above left) and boldly placed right in the centre of the site: it stands below and between the tombs of Darius I and the tomb attributed to Artaxerxes I (as seen at the top of this post), and right across from the Ka'ba. This relief shows Shapur on horseback grasping the wrist of Valerian -- which indicates he has been taken prisoner -- while Philip the Arab is kneeling in submission before the King.

... and just as we, with the help of the gods sought out and conquered these lands, and did things of fame and daring, so let him too who shall be ruler after us be conscientious in the concerns and cult of the gods, so that the gods may make him their creature too.

Sasanian King# 3

The third king to leave his mark at Naqsh-e Rustam was probably Bahram II (276-293 CE) [despite not being inscribed,the reliefs attributed to this king are based on the shape of his crown].

The reliefs, inscriptions, and appropriations of Ardashir I and Shapur I changed people's experience of the ancient site -- and would greatly influence the monumental legacy of Sasanian (Recovered) Memory. Their successors inherited visual traditions of Achaemenid and Sasanian monuments that became ever more thoroughly fused. Future reliefs responded to earlier reliefs by moving back and forth in time. Later kings became increasingly sensitive to the placement and shape of the earlier reliefs, forging constant visual interactions across the centuries.

Just so, Bahram II lined up his double 'jousting scenes' -- more accurately, scenes of equestrian combat -- directly under the tomb of Darius the Great, extending the long vertical arm of its cruciform shape. It seems evident that he saw himself as a true descendant of the tomb's original occupant and his victory reliefs (for he is the clear winner on both) as adding honour to his ancient Persian ancestors.

By this time, in a sense, Sasanian kings had blurred the two dynasties' visual culture completely. What now drew people to the site -- the Achaemenid remains or the Sasanians' reinterpretation of it?

Who knew anymore?

* The modern name for the valley, meaning 'Pictures of Rustam': Rustam/Rostam is the legendary Persian hero later thought to be depicted in the jousting scenes.

** A suggestion made by Jona Lendering (Livius.org).

My main source for this post (as for Part I) is Matthew P. Canepa, 'Technologies of Memory in Early Sasanian Iran: Achaemenid Sites and Sasanian Identity',American Journal of Archaeology, 114 (October 2010) 563-596; and when I am directly quoting, I am quoting from him. Other sources include M.P. Canepa, 'Shapur I, King of Kings of Iran and Non-Iran', Ch. 4, in The Two Eyes of the Earth: Art and Ritual of Kingship between Rome and Sasanian Iran (Univ. of California, 2010) 53-78; Livius.org pages on Naqš-i Rustam, and Sasanian Rock Reliefs; Encyclopaedia Iranica; and the Naqsh-i Rostam page by Ursula Seidl at CAIS.

Illustrations (in descending order)

Top centre: Achaemenid tombs of Darius I (right) and Artaxerxes I (?). Photo credit Travelpod

Ka'ba Zoroaster: Photo credit: Wikipedia (Fabienkahn)

Investiture and triumphal rock relief of Ardashir from Livius

'Roman Victory' rock relief of Shapur from Livius

Detail of tomb of Darius I (above) with victory scenes of Bahram II (below). Photo credit: Iran Politics Club

.

.

.