Exploring Zenobia's World. The Incredible Rise and Fall of the City of Palmyra

08 February 2011

Gods At the Crossroads (Updated)

Where in the world will you find texts written in Greek, Latin, Palmyrene and Syrian Aramaic, Middle Persian, Parthian, Hebrew, and Safaitic -- all inscribed at much the same time? And where do you think you will come across dozens of temples dedicated to Greek and Roman gods, a bevy of Mesopotamian deities (some of dazzling obscurity), Palmyran gods and gads*, a Mithraeum, a frescoed synagogue and the earliest Christian house-church anywhere in the world?

Perhaps in Rome, you would guess.

But no, not Rome.

Rather, at a distant outpost on the Euphrates frontier, in the ruined city of Dura Europos:

The town (today in Syria) is perched on a hill high above the river. Its name, Dura Europos, is an artificial twin, joined by archaeologists to describe the city known to Parthians and Romans as Dura (meaning 'fortress') and to Greeks as Europos -- in honour of the Macedonian birthplace of Seleucus Nicator, a general under Alexander the Great, who is reputed to have founded the city.

At the Crossroads of East and West

Seleucus Nicator (358-281 BCE), the first king of the Seleucid dynasty, filled the town with Macedonian veterans in order to control the strategic river crossing and to connect the equally brand-new cities of Antioch near the Mediterranean coast with Seleucia on the faraway Tigris (near modern Baghdad)

The Parthians conquered Dura in 141 BCE and it remained in their hands -- except for a brief grab by Trajan ca. 115 CE -- until captured by the Romans in 165 CE, after which it was garrisoned by Roman and Palmyran troops (the latter, a cohort of horse-mounted archers, the XXth Palmyrorum). Dura met its end after a sustained siege by the Sasanian Persians in 256/57 -- after which it was abandoned, covered by sand and mud, and disappeared from sight.

Treasures on Display

Between 1928 and 1937, archaeologists from Yale University and the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres excavated Dura, bringing to light not just the temples, houses, fortifications, and military quarters of this cosmopolitan city, but an extraordinary collection of frescoes, mosaics, and carved reliefs, as well as inscriptions in a babble of languages and astonishingly well-preserved objects of war and peace, all mingled together in the daily life of a bustling town.

Now, an exhibition at the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College is showcasing some of the most significant treasures excavated in the 1920s and 1930s from the ancient city: Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity displays 75 artefacts from the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery. Together, they tell the story of this vibrant multicultural city inhabiting a crossroad between major eastern and western civilizations.

Crosscurrents in a microcosm

I'd like to showcase just one piece that caught my eye (below). Of course, there's a good Palmyran story behind it, too.

The foundation of the city was still being celebrated in 159 CE (that is, still in the Parthian period) -- not just by descendants of those first Macedonians, but by Palmyrans living at Dura. Expatriate Palmyrans dedicated this handsome stone relief at the Temple of the Gads* (Tyche in Greek; the 'Good Fortune' of the city), which they had built at Dura -- more than 200 km as the crow flies from Palmyra. Inscriptions, primarily in Aramaic, identify the figures and date the dedication.

The relief depicts the Gad* of Dura as a bearded Zeus Olympios dressed in semi-Greek costume. The god/gad is seated on a throne flanked by two eagles; a throne flanked by duplicated birds or animals is not at all a Greek idea but rather reflects a very ancient Near Eastern divine custom.** The reputed founder of the city, Seleucus Nicator, in military outfit, is seen crowning the god. Zeus was that king's divine patron and the relationship between the king and his favourite deity remained intimate long after his reign, even extending to a royal cult of Seleucus Zeus Nicator. A Palmyran priest, named Hairan, burns incense on an altar to the left of the scene(besides his Semitic name, Hairan wears a tall cylindrical cap, the sign of a Palmyran priest).

Outsider Offerings

So, the first thing to note is that we have a group of outsiders (= Palmyrans; probably merchants, for their temple is quite near the main marketplace) who are showing respect to the major god/gad of their place of residence. And, while the relief honours the Greek god/gad as Dura's highest deity and equally relates to the cult of the Seleucid dynasty, the offering is made by a Palmyran priest. And, of course, the relief will hang in the main Palmyran temple at Dura.

That's not all we can read on this relief.

The second thing to note is that it was made of Palmyran limestone so it had been ordered and (from the look of it) carved in Palmyra and transported to Dura. It was probably made to mark an event that took place before the end of the Parthian period -- and that must have been connected with the rebuilding of the Temple of the Gads ca. 150 CE. The new, expanded temple was double the size of the original, modest religious structure established a century earlier. Most, if not all, of the construction work was financed by one important Palmyran family: that of Hairan, the son of Maliku, son of Nasor. That's the same Hairan who offers incense to the Gad of Dura on the relief above. This rich aristocrat, by the way, is almost certainly the great-grandfather of Zenobia's husband, the heroic warrior prince, Odenathus.

Sex Change at Dura

A male 'Fortune' of a city is incompatible with the Greek notion of Tyche but fits the Semitic tendency to view the most important deity of a locality as its gad. Despite Dura-Europos being ruled by the Parthians for almost 300 years, the iconography of the gad and the figure of Seleucus Nicator suggest that the Palmyran residents of Dura considered the main god of the city to be the Greek god, Zeus Olympios; evidently, they still thought of Dura as a Greek city. This surely was not a Palmyran invention but must have been the common idea elsewhere current in the city. In short, the indigenous inhabitants of Dura continued to cherish their Macedonian/Greek heritage and identity right through the Parthian period.

Semitic Gads were inextricably connected with a particular place or people ... but, apparently, at Dura, not necessarily with a particular sex.

Because of their origin in the Greek goddess Tyche, Syrian Tychai, too, are always represented as female -- whereas the Semitic gads, being manifestations of locally venerated gods and goddesses, can be either male or female. Yet, by the Roman period at the latest, Dura's Fortune of the City is being venerated as Tyche (Greek), gd (Palmyrene), or genius (Latin); and all three 'names' can appear together even on a single altar, which shows that they have become indistinguishable. This may well be due to the popularity of Tyche in other Greek cities, not least at Antioch, the greatest city of Syria.

So, the gad of Dura undergoes a sex change

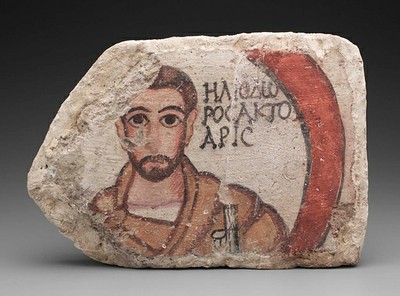

This famous fresco [also from the Palmyran Temple (ca. 239 CE)], shows Julius Terentius, the tribune of the Palmyran cohort, offering incense to three Palmyran gods (upper left) and to the gads of Palmyra and Dura (lower left). Both gads are represented as goddesses. This change of the sex of the Gad of Dura may reflect a shift from the old Semitic idea that the most prominent local deity is automatically the local gad to the Greek convention of identifying the Fortune of a city as female. And so, like any good Greek city goddess, the two gads are depicted wearing mural (city) crowns.

The mural crown (left) identifies the Fortune of the City as surely as the cylindrical cap marked our Palmyran priest, Hairan. Henceforth, the Dura goddess, whether she is labelled as Tyche, gad, or genius, will appear with this crown -- as you will spot on several examples if you are lucky enough to get to Boston to see Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity.. It runs from today (well, actually, from 5 February: I'm a wee bit late) until 5 June, 2011. Catch this spectacular show if you can.***

Updated 22 September 2011

Diversity of Cultures in Ancient City of Dura-Europos Explored in Special Exhibition at NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW)

Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos moves to New York as of tomorrow. Lucky New Yorkers -- and visitors!

Exhibition Dates: Sept. 23, 2011 – Jan. 8, 2012

Chief Curator Jennifer Chi says, “The site of influential archaeological finds, Dura is an apt subject to be explored by ISAW, which is dedicated to illuminating the connections among various places and cultures of the ancient world. Moreover, as a city of extraordinary cultural diversity, Dura has great resonance for the modern world, where multiculturalism shapes the very nature and quality of daily life.”

Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos will be accompanied by a new catalogue with essays by leading scholars, a map of the region, archival photographs of excavations at Dura, and a checklist of the exhibition. Published by the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, the soft-cover catalogue will be available for $25 at the Institute and through Princeton University Press, its distributor.

Additional information: Edge of Empires website

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

New York University

15 East 84th Street

New York, NY 10028

Hours: 11am-6pm

Friday: 11am-8pm

Closed Monday

Free Admission

The ISAW presentation has been made possible through the support of the Leon Levy Foundation.

* Gad is an Aramaic word meaning 'luck' or 'good fortune' and can refer to a divine being, most commonly the tutelary god or goddess of the city. The temple is now usually called the 'temple of Bel'.

** While the eagle is a typical attribute of Zeus, the Greek god has one eagle, not two, which either sits on his hand or beside his throne. The duplication and placement of the eagles flanking the throne is oriental in origin.

*** If you can't make the show, the exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue of the same title, which includes 18 scholarly essays by an international group of participants and a colour plate of each object on display. With a range of specialists—from Yale, Boston College, Harvard and Brandeis universities, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and universities in Great Britain and the Netherlands, the catalogue — like the exhibition — seeks to reintegrate thinking about the city of Dura-Europos.

I am grateful to Margaret Neeley, Publications & Exhibitions Administrator,McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College for sending me the excellent press kit and photographs. Co-curators of Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity are Yale University Art Gallery Associate Curator of Ancient Art Lisa R. Brody and Boston College Assistant Professor of Classical Studies Gail L. Hoffman.

I have made much use of Lucinda Dirven's discussion of the 'Hairan relief' in her book, The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: a Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria (Brill, 1999), Ch. 4. For more information on Dura Europos, see Simon James' pages at the University of Leicester website.

Illustrations

The photo of the citadel at Dura Europos is from University of Leicester. Other photo's are courtesy of the McMullen Museum of Art.

.

.

.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment