And why does it matter now?

This is a Sasanian-Persian soldier, probably a ranking officer (his upper body was protected by iron mail armour and he carried a sword with a pommel of jade, a semi-precious stone that can be tracked to Chinese Turkestan). He died a gruesome death in a claustrophobic tunnel below the walls of Dura-Europos in a fire that he may have intentionally set. His men were mining under Tower 19 (not far from the Palmyra Gate) when a Roman countermine broke through and enemy soldiers entered the tunnel.

What happened next is hotly contested.

In fact, it almost caused a diplomatic incident when Dr Simon James of the University of Leicester presented a new theory to an American archaeological congress in 2009. He argued that the soldier was a victim of 'friendly fire' as a poison gas attack against the Romans backfired on him. The Islamic Republic of Iran denounced his story as a deliberate defamation of its history linked to western pressure on Iran over its nuclear program. But wait a minute! This guy died (and Dura fell) in 256 CE -- almost 1,800 years ago. Why get hot under the collar in 2009?

It's complicated.

But now that Dr James has fully published his 'Gas Warfare' hypothesis in the American Journal of Archaeology,* you can judge for yourself.

The Story So Far

The fortress city of Dura-Europos lies on the Middle Euphrates at what was the eastern edge of the Roman Empire (for background, see my post, Gods at the Crossroads). Founded by the Seleucids in ca. 300 BCE, it was taken by the Parthians in 141 BCE and it remained in their hands, almost continuously, until captured by the Romans in 165 CE, after which it was garrisoned by Roman and Palmyran troops (the latter, a cohort of horse-mounted archers, the XXth Palmyrorum). They held it until 256/7 when it was destroyed by the Sasanian-Persians after a gruelling siege, its inhabitants either slaughtered or sold into slavery, after which the city was abandoned, covered by sand and mud, and disappeared from sight.

Four years earlier, the Sasanians had invaded Syria, one of Rome’s richest provinces, taking the capital, Antioch, before withdrawing from the region. In response, the Romans massively strengthened the defences of Dura to block the Euphrates road into the province.

|

| Area of Tower 19 prior to siege |

|

| Area of Tower 19 with full defensive works |

The anticipated attack came in 256, probably in the spring, and it must have lasted at least several months since it involved major Sasanian engineering works. The Sasanians used the full range of ancient siege techniques to break into the city, including mining operations to breach the walls and bring them down. Roman defenders responded with countermines to thwart the attackers. The determined resistance put up by the inhabitants forced the assailants to adopt various siege tactics, which eventually resulted in conquest of the city; the defensive system, the mines, and the assault ramp were left in place after the deportation of the population.

The Persian Offensive

Several points of assault have been identified along the western defences, probably pushed forward in parallel to overstretch the defenders (red arrows in aerial view above and left).

Ferocious but apparently unsuccessful attacks took place in front of the great Palmyra Gate. At the southern end of the wall, a massive siege ramp was constructed 40 m long (120') and 10 m (30') high against the wall to permit troops to enter; it consisted of a mass of rubble packed between two walls of bricks and paved with baked bricks, which made it possible to move a siege machine close to the wall. Two tunnels, each wide enough to permit several men to advance abreast, were dug near the body of the ramp. Attacks also involved sapping and tunnelling to get troops into the city under nearby Tower 14.

The remaining known target of attack was around Tower 19.

The Battle for Tower 19

One of the French excavators of Dura in the 1920s and 1930s,** Robert du Mensil du Buisson, himself a military officer, concentrated especially on the remains of the final siege. In a narrow, low gallery under Tower 19, he discovered dramatic evidence of combat and death underground:

Here, lying in a Roman countermine intended to disrupt Sasanian attempts to undermine or sap the city defenses, du Mesnil found a tightly packed tangle of up to 20 bodies he identified as Roman soldiers, still with their equipment and their last pay in their purses, and nearby another armored skeleton interpreted as one of the Sasanian attackers.*

This is the 'crime scene' (left) that Simon James has now re-examined in an attempt to understand exactly how these Romans died, and came to be lying where they were found.

Persian Tunnelling

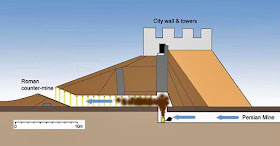

Their objective was to create a large breach in the city defences by undermining part of the wall, making a gap wide enough for their troops to charge from the Persian lines across the open plain to pour into the town. The miners would sap Tower 19 at the same time in order to eliminate Roman defensive fire in that area. To reach the walls, however, the Persians first had to dig a 40 m (130') long narrow, timber-propped approach tunnel from their own lines facing the city. When the tunnellers got under Tower 19, they cut an upward shaft to reach the foundations of the defences, which they began to undermine.

Roman Countermining

As the Persian miners came closer to the walls, the defenders could hear them at work (and also probably see their spoil heap rising on the plain) and so began to dig a countermine -- equally propped with timber posts and lintels -- intending to break into the Persian sap and halt their operations. This countermine was dug through their own earth rampart behind the city wall and ran along the north side of the tower. As discovered by Dr James, this tunnel was about 3 m (10') above the level of the Persian mine.

The Romans were out of luck that day. When they broke into the Persian tunnel, instead of capturing and holding it, their own tunnel was taken and destroyed, allowing the Sasanians to fire the mine: filling the tunnel with straw and bundles of wood, they ignited it, adding incendiary elements such as sulphur crystals and bitumen (a naturally occurring tar-like substance) to make it burn hotter, traces of which were found by the excavators in the tunnel. The blazing fire incinerated the wooden struts, causing the wall and tower to slump into the Persian mine -- severely damaged, but neither collapsed thanks to the supporting mass of the glacis and rampart [when removed by the archaeologists, the effects of the mining were brought to light; above].

The Persians would have to start all over, elsewhere.

The underground battle at Tower 19 ended, leaving in the tunnel 20 dead Romans and 1 dead Persian. The burning question: How did they die?

Here's du Mesnil's reconstruction of events (with some commentary of mine).

1. When the Romans broke into the Persian tunnel, there was a fight and the Romans were driven back into their own gallery, the Persians in hot pursuit. The Persian officer was killed in this skirmish.

2. The Romans inside the town, seeing their miners fleeing from the tunnel (surely shouting something like "Aaagh, the Persians are coming!"; in any case in panicked disorder) hurriedly blocked up the entrance to the counter-mine, not noticing -- or caring -- that they shut in some of their own men.

3. The Persians were too few to enter the city; they would have been fools to try as they would have been cut down as they emerged one-by-one from the dark, cramped tunnel, barely high enough for a man to stand upright. Instead, they set fire to the countermine and rapidly withdrew. The trapped Romans, judging from the tangle of their bodies near the blocked entrance, were either killed in combat, suffocated by the fire, or died in the flames or when the roof of the tunnel collapsed. Not a pleasant fate, in any case.

No, says Simon James: that's not the way it happened, not at all.

Dr James has gone back and (figuratively) untangled the 'body stack'. Rather than sitting or standing when they died, his drawings show

a number of the lowest bodies sat up against the sides of the gallery with their legs outstretched across it -- not defensively contracted as we would expect if other, hobnailed comrades were standing over them. Other bodies lay on top of these, mostly stretched across the mine on top of others. How could these have ended up in such a posture, if crammed among comrades collapsing together from a standing position?James argues that they had been deliberately dragged to this point and piled up, stacked at least three or four bodies high. In his scenario, the Romans did not block the entrance. Rather, the Persians, finding about 20 dead or dying Romans on the floor of the Roman tunnel, with brutal practicality, "turned these obstacles to advantage by carrying the bodies and shields toward the countermine entrance, where they piled them into a barrier, hindering any further Roman attack...." In other words, they used them to build what the British army calls 'organic sandbags' -- and then went about preparing their fire.

How Did These Romans Really Die?

It seems inconceivable, says James, that they could all have fallen in hand-to-hand combat in such a confined space ... nor does the disposition of their bodies suggest that they were trapped by their own side (as du Mensil supposed).

What happened, he says, was this:

Just as the Romans heard the noise of the Sasanians working beneath the ground as they neared the walls, so the Persians heard the Roman counterminers approaching and planned a nasty surprise for them.

As pictured left, they placed a brazier (a pan for holding hot coals) in their own tunnel below the shaft leading up to the tower (where they had started removing foundation stones). As the Romans broke through, the Persians retreated into their approach tunnel and threw onto the brazier "some of the bitumen and sulphur crystals we know they had because they were using them, probably just minutes later, to set fire to the Roman tunnel."

When these chemicals are burned in a controlled fire, the highly inflammable bitumen and sulphur crystals combine to create sulphur dioxide, a poisonous gas, that turns to acid in the lungs when inhaled.

Whether the Sasanian engineers pumped these fumes up into the Roman tunnel with bellows (as he thinks probable) or a natural chimney effect drew the hot gasses upward from deeper Persian tunnel into the higher Roman gallery, the result was the same: those who inhaled the deadly fumes would have been choking to death in a matter of seconds.

I think the Sasanians placed braziers and bellows in their gallery, and when the Romans broke through, added the chemicals and pumped choking clouds into the Roman tunnel. The Roman assault party were unconscious in seconds, dead in minutes. Use of such smoke generators in siege-mines is actually mentioned in classical texts, and it is clear from the archaeological evidence at Dura that the Sasanian Persians were as knowledgeable in siege warfare as the Romans; they surely knew of this grim tactic.

"Any Roman soldiers waiting to enter the tunnels would have hesitated, seeing the smoke and hearing their fellow soldiers dying," James said. "It would have almost been literally the fumes of hell coming out of the Roman tunnel."

Meanwhile, down in their approach tunnel, the Persians needed only to wait until the noise above them stopped and the smoke cleared. Then they went up, found the dead and dying, stacked them, and started the fire that collapsed the gallery. But one man paid the price for their invention of chemical warfare: the Sasanian officer who started the fire (perhaps he knelt to ignite the combustibles and accidentally inhaled a mouthful of noxious fumes) collapsed backward, grasping desperately at his chain mail shirt as he choked, and the fire partly consumed his body before the roof fell in on him and the Roman dead.

Where There's Smoke

|

| The Tunnellers' War 1914-1918 |

Aside from that, it's a very satisfying story. But is it true?

The elements are all there: the configuration of the two tunnels, the body stack, the dead Sasanian soldier, and, above all, the sulphur crystals and bitumen. It could have happened that way, but did it?

I have my doubts.

First of all, the success of the operation would surely have led to it being repeated by the Sasanians. We have 400 more years of almost constant warfare between Persia and Rome (and later Byzantium), regularly punctuated by devastating sieges, and not a single mention of the devilish Persians using poison gas or even smoke machines.*** And if they had used it, the Roman military would have adopted it sooner or later, too. So we would be fairly likely to hear rumours of poisonous smoke attacks. We don't. Fire, yes; burning naphtha, yes; poisons, yes; poison gas, no.

Second, it depends how idiotic we think that Sasanian officer was. Knowing that he was lighting a fire with noxious chemicals, he takes off his helmet, puts aside his sword (as if he had all the time in the world), ignites it ... and takes a deep breath. I don't think so.

Third, James suggests that the Roman officers outside the tunnel did not block their tunnel entrance, thereby trapping the 20 men, "because they could not or because they contemplated a renewed assault." But wouldn't they have been oddly negligent if they did not have blocking materials to hand? They couldn't know how large a tunnel the Persians had dug until they broke into it. Rather, picture wounded men coming out after a skirmish in nightmarish dark (possibly already thick with smoke) and it's not difficult to imagine a rapid decision to block it. It's no worse, I suppose, than closing the gate on men still fighting outside the walls and leaving them to their fate. Cruel stuff happens.

Alternatively, I suggest a modified du Mesnil scenario. Most Romans were backing out of the tunnel when the Sasanian officer starts to light the fire. A Roman soldier stabs him and runs to the exit to find his escape blocked. All the men trapped inside would naturally cluster at the blocked exit, shouting for help, the wounded stretched on the tunnel's floor, the fit standing until overcome by smoke, falling one after the other, this way and that, exactly as they were found -- and indeed as they appear in Dr James' drawing. The roof falls in before the Persians can retrieve their dead comrade.

I'm not saying this happened, of course. It could have been entirely unexpected that the gas released by the fire turned poisonous and killed the Sasanian officer as well as the 20 men hovering near the blocked exit. If so, the Persians didn't realize what had happened and the identical circumstances never arose again.

We'll probably never know.

Update 11 June 2011

WWI underground: Unearthing the hidden tunnel war

Archaeologists are beginning the most detailed ever study of a Western Front battlefield, an untouched site where 28 British tunnellers lie entombed after dying during brutal underground warfare.

When most people think of WWI, they think of trench warfare interrupted by occasional offensives, with men charging between the lines. But with the static nature of the war, military mining played a big part in the tactics on both sides. What happened at La Boisselle in 1915-16 is a classic example of mining and counter-mining, with both sides struggling desperately to locate and destroy each other's tunnels. The tunnel networks (seen here, above left) extending far from the trench system to reach enemy territory were complex and extensive. Though they could not see each other, in places the two sides were just metres apart.

Archaeologists, historians and their French and German partners now aim to preserve the area - named the Glory Hole by British troops - as a permanent memorial to the fallen. Digging does not start until next year, but the first practical steps of mapping the tunnels and trenches using ground-penetrating radar, and exploring the geophysics are under way.

Peter Jackson tells this fascinating story on the BBC News Magazine.

* S. James, Stratagems, Combat, and 'Chemical Warfare' in the Siege Mines of Dura-Europos, AJA 115 (2011) 69-101.

** Initial archaeological exploration of the city was carried out by the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres of Paris in 1920-22. From 1929 to 1937 Yale University and the Academie sponsored the excavations.

*** During the siege of the Greek city of Ambracia in 189 BCE, the Romans were driven from a mine that already reached under the city wall by acrid smoke from a jar filled with feathers and hot coals which was blown into the tunnel by means of a bellows (See Paul B. Kern, Ancient Siege Warfare [Indiana UP, 1999] 275-7). In the 4th C BCE, Aeneas Tacticus wrote a treatise on war which specifically mentions using smoke to drive enemy troops out of a tunnel or even suffocate them (ibid 182). On this subject, see now Adrienne Mayor, Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World (Overlook Press, 2003).

Sources for this post (in addition to Simon James' AJA article and his Dura webpage) include Pierre Leriche, current director of excavations, on Dura-Europos, at CAIS; Jordan Lite writing in the Scientific American; and Stephanie Pappas at LiveScience.

Illustrations

Top left: The body of a Sasanian attacker, still clad in his iron mail shirt, helmet and sword near his feet. Image credit: Yale University Art Gallery, Dura-Europos Excavation Archive (via InSciencesOrg)

Middle left 1: Aerial view of the walled city of Dura-Europos (modified by blogger). Photo credit: IoArch.it

Middle left 2: Newly reconstructed sequence of construction of rampart and glacis at mine site (Tower 19) prior to siege (modified by blogger): from Simon James website.

Middle left 3: Plan of the site under Roman rule (modified by blogger): from Simon James' website.

Middle left 4: New composite plan of the Roman countermine, showing the stack of Roman bodies near its entrance, the area of intense burning marking the gallery’s destruction by the Persians, and the skeleton of one of the attackers (photo: Simon James, via InSciencesOrg).

Middle left 5: Damaged walls and tower structure (Tower 19): from Simon James' website.

Bottom left: Diagram of proposed gassing of Romans at Dura-Europos (photo: Simon James, via Scientific American)

.

.

.

Brilliant post Judith and it opens up so many possibilities. I wouldn't write off the James scenario just because there's no evidence it happened again. Poison gas was used in WWI, but it hasn't been used since for reasons that are partly practical and partly political

ReplyDeleteThanks Doug,

ReplyDeleteAfter WW I, the Western powers agreed never again to use poison gas (and that became an international convention) but Saddam Hussein broke the rules, using gas in the Iran/Iraq war and against civilian Kurds; and, needless to say, there are large stocks of chemical and bio weapons kept by several powers and wannabe powers -- just in case. The Roman and Persian armies were brutal and, in our terms, ruthless. I cannot see (from the 3rd C on) anyone protesting that poison gas was not honourable: what is the moral difference between throwing boiling oil or burning naphtha on the enemy and smoking them out 'with extreme prejudice'? Who would worry about if if you won?

Zenobia's story is fascinating. She has a very strong personality.

ReplyDeleteWould be extraordinary if hollywood made a movie about Zenobia and the people of Palmyra.

Judith, would be fascinating if Zenobia give your research a film director. I'm sure you will love. The story of Zenobia have much content.

I want to help.

Zenobia's story is fascinating. She has a very strong personality.

ReplyDeleteWould be extraordinary if hollywood made a movie about Zenobia and the people of Palmyra.

Judith, would be fascinating if Zenobia give your research a film director. I'm sure you will love. The story of Zenobia have much content.

I want to help.

Adriana

My email: ahamida1@hotmail.com

I too find it hard to believe, Anonymous, that no filmer has picked up on her wonderful -- and colourful -- story. It would be great for the cinema. Any help would be greatly appreciated.

ReplyDeleteFascinating post! Your proposed "accident" scenario sounds most plausible to me of the available options. I can't help but think, however, that James' hypothesis does account best for the strange positioning of the Roman soldiers.

ReplyDeleteWith that in mind, here's my question: if the Sasanians had indeed employed this tactic again, how would archaeologists distinguish it from the common practice of smoking out miners? Is it possible, then, that this just happens to be an example where it CAN be distinguished? This might provide James with a defense.

Of course, I don't have the archaeological or chemical training to know the answer to this - but just curious!

Again, phenomenal post!

Thanks for the kind words, Ari.

ReplyDeleteYou're quite right that James' untangling of the skeletons is impressive evidence but I am sceptical how much you can read into that. Imagine the pile-up of wounded and panicked men at the (blocked) exit of a pitch dark tunnel, then overcome by smoke of any origin, and I think you'll have much the same distribution. 'Not proven' I would say.

Almost certainly archaeologists would not find similar evidence of sulphur and bitumen elsewhere. Dura is unique in its remains because 1) it was never again inhabited (which is very rarely the case; and 2) so much was preserved *under* the glacis and the inner rampart.

Which is why I emphasized the lack of written evidence: in the long, highly charged political and religious conflict between Persia and Rome, it seems odd that such a 'dirty' tactic was neither mentioned nor copied. By itself, this does not prove anything ... but I think it does put the onus back on the poison-gas proponents.

Judith

PS: I lean towards the accidental explanation, too.

Sorry to beat a dead horse... but I just came across this blog. This story has fascinated me, and your interpretation was very compelling. As a fire protection engineer who deals with reconstruction analyses, I would like to shed light on some technical aspects that don't seem to have been investigated.

ReplyDeleteSulfur is naturally found in bitumen, so I am interested as to why it was assumed that it would be added to the fuel, unless the sulfur crystals found clearly came from another source. While this would certainly make the resultant products of combustion more toxic, I would expect sulfur to be found in the majority of unprocessed bitumen. Without any analysis, I can't say for sure, but I have doubts that the levels of sulfur naturally found in bitumen would produce a lethal dosage when burned.

Assuming your interpretation is correct (which I also lean towards), I would argue that almost any fuel would create the same result, even just plain wood and hay. Without going into compartment fire dynamics in detail, a fire of this nature would quickly turn into an under-ventilated fire, meaning it is oxygen limited. Further enclosing the tunnel would both increase carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide production, as well as deplete the oxygen concentration. Hypoxia and/or CO poisoning could cause incapacitation or death, with carbon dioxide increasing the respiratory rate, speeding up the process. Depending on fuel content and the size of the fire, thermal exposure, as well as other toxic products could be a factor.

While these may not be the poisonous gases envisioned, they are the most typical culprits in fire-related deaths, and can act very quickly.

As for the ventilation issues discussed, hot smoke (along with it's toxicants) will travel upwards, even with no exit, due to buoyancy. The chimney effect would increase the velocity of the smoke, and bring fresh air to the fire, assuming both sides are open.